As my interest in cooking grew when I was younger, my mum and I loved experimenting together. One of my favorite things to make during this early experimental phase was spring rolls – Chinese-style….or Chinese-style-ish. The stuffing was easy enough, and definitely Chinese-style; we were all vegetarian, so our filling of choice was a simple stir fry of cabbage, carrots, onions, garlic, ginger…that was pretty easy for us to recreate from our experiences eating spring rolls on our Chinese meals out. That was also the time I discovered that soy sauce is salty. Discovered it the hard way – by salting the food regularly, then adding the soy – because how could we have Chinese food without soy? We had throw out that batch of filling. Subsequent batches, however, were delicious. But the wrappers, those were a different story; hence my Chinese-style-ish. See those weren’t the days of store-bought wrappers yet. So experiment, we did. Samosa wrappers (homemade, of course) didn’t seem quite right. And didn’t work well. And it was then that my mum had the idea to create wrappers out of crepes. They wouldn’t be crisp and fried, she said, but I think they’ll work. So we made a simple crepe batter – nothing exotic there – eggs, flour, milk, blended together. Then we made crepes – we’d made those a million times before because of our time in Edinburgh (my favorite way to eat a crepe is still with a bit of fresh lime or lemon juice and a sprinkling of sugar). Then we’d put a bit of our filling on the crepe, and fold the sides over to create a package – a rectangular package, which we’d then crisp up a bit on either flat side. Not exactly a spring “roll” – but man oh man, were they ever delicious.

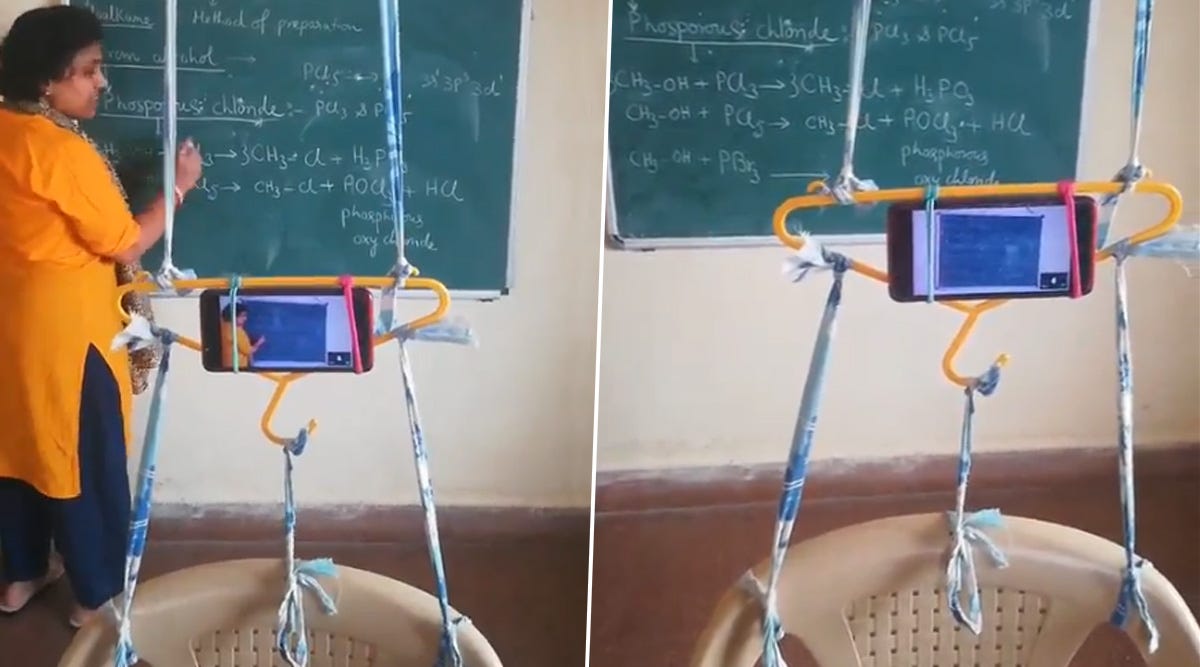

So a few months ago, I learned the Hindi word jugaad – which has even made it into Wikipedia. It is a noun, (I’m also using it as a verb…call it…er…my linguistic license), and the adjectival form seems to be jugaadu. Now while I haven’t become familiar with all its grammatical intricacies, its meaning is clear: jugaad means an innovative fix, an inexpensive solution, sometimes (or often) involving a bending of rules (and let’s not get into pesky safety issues here). The term is used to describe the creativity and flexibility of Indians in finding solutions to difficult or expensive problems –just making something work. Adjusting, adapting, most often entailing the recycling of materials. And popular media (and increasingly, the term has gained interest in academic circles, too) is as rife with examples of Indian jugaad as well as jokes about Indians’ propensity of re-using materials, from plastic bags to coffee containers to old sarees – all jugaad, all innovative, all to make our lives easier. A way of maneuvering and negotiating the world through improvisation. And all jokes aside, the innovations are, almost invariably, brilliant. We’re not talking about safety, remember?

My favorite is the kids’ bike seat.

And I have spoken at least a couple of times before about our ability to adjust the English language to suit our purposes; the coining of new words, phrases, combining two languages – and thereby making English ours. And that is nothing if it isn’t jugaad. Adjusting the language to suit our needs. While I have given you several examples in earlier posts, here’s another fun one – this time, not a linguistic innovation, per se, but a play on a name.

Siblings of the American 7-11, if you will. Bloody brilliant.

So what does this all have to do with the spring rolls I began this post with? This.

Last week, for the first time, I heard the word jugaad used in a culinary context. And it took me right back to our crepe-spring roll-making days. I encountered the word used by someone on one of the many food groups I am a part of, to describe an Indo-Chinese (which itself is jugaad) dish she’d made with whatever she’d had on hand. She was missing several ingredients, but liberally substituted, to create what she said was exquisite. Not the original, but fantastic.

And I have, thus far, spent a considerable amount of time applauding this ability to mix cuisines, to create new cuisines, new flavor combinations. Because why not? And I have also waxed lyrical about using whatever we have available to make a dish – don’t let the lack of a certain ingredient prevent you from trying something new. I’ve always believed this.

Now I think all of us – or those of us who have an interest in cooking - do have a somewhat jugaadu attitude. And for me, this is lovely. This aspect of cooking is, for me, one of the most pleasing.

But.

Today, I’m going to focus on what I think could be a problem with this tendency. Because at its heart, while it is creative, most often, it can also be reductive. Because by being jugaad and making do with what we have, aren’t we essentially removing a certain complexity (not to be read as necessarily complicated) from the dish and making it less distinctive? Now this ability of ours to simplify, to adjust, is probably one of the reasons for the popularity of Indian food across the globe. The popularity of curry. Yes, the yellow, slightly spicy saucy stuff. And if you asked anyone not very familiar with Indian cuisine what they thought went into it, one immediately answer would be curry. And maybe turmeric. The lowest common denominators, if you will.

So while I most certainly would encourage someone unfamiliar with Indian cuisine to try recipes despite possibly not having all the ingredients in their kitchen, I urge those with a fondness for Indian cuisine to venture beyond the lowest common denominator. To not be jugaadu. Not always, at least.

And with that, I give you a recipe I could very well give you jugaadu options for, but one that I ask you to try in its original form. It is a simple dhal. One made with a veg (this time, cilantro because it’s my favorite), and that gets its name from the ingredients and technique – fresh coconut, red chillies, and urad dhal fried together in a wee bit of oil, then ground to a paste; the dhal is then mixed with the veg of choice and flavored with this paste. This is a Tamilian porichakozhambu.

And the jugaadu options: Use masoor dhal (orange lentils) instead of toor dhal; substitute the coconut with coconut milk; use a wee bit of cayenne or Kashmiri chilli powder instead of the dried red chillies. And if you did this, and left out the urad dhal altogether, it would still taste amazing. But it simply wouldn’t be a porichakozhambu.

And a porichakozhambu, as simple as it is, is a thing of beauty. Every single time I have made it for non-Indian friends, even those very familiar with Indian cuisine, I’ve always had the same reaction: why do the dhals we typically eat never taste this good?

Because you can’t jugaad everything.

Cilantro Porichakozhambu

Ingredients

1. ¾ cup toor dhal. If you don’t have toor dhal, or want to use an easier-to-cook dhal, you can use masoor dhal (the orange lentils) instead

2. 3 cups of rough-chopped fresh cilantro

3. 1 Tbsp coconut oil

4. 3-4 dried red chillies (more if you want it spicier)

5. 1 cup unsweetened coconut – either fresh or dry

6. 1 Tbsp urad dhal (white lentils)

7. 1 ½ tsp salt

8. ½ tsp sugar

9. 1 Tbsp fresh lime juice

10. 1/2 tsp turmeric

For Tempering:

1. 1 ½ Tbsp coconut oil

2. ½ Tbsp mustard seeds

3. ½ Tbsp cumin seeds

4. 2 sprigs of curry leaves

5. ¼ tsp asafoetida

Method

1. The cooking method I am describing here for boiling the dhal is for those of you who don’t have a pressure cooker. If you do have a pressure cooker, simply cook the dhal with 2 cups of water and turmeric in a pressure cooker.

2. So if you don’t have a pressure cooker: Rinse and soak the toor dhal in 2 to 2 ½ cups of boiling water. This helps reduce the cooking time. Allow it to soak for 30 minutes.

3. Now add ½ tsp turmeric to the soaked dhal and boil it with its soaking liquid with a lid on. Boil on medium to low heat, stirring occasionally to prevent the water from boiling over. If it gets too thick, add an additional half cup of water. It should take about 30 to 35 minutes to cook, at the end of which the dhal is well-boiled and mushy. For Indian dhals, the lentils should be completely boiled and not have a bite to them.

4. While the dhal is cooking, boil the chopped cilantro with 1 tsp salt and ½ tsp sugar in ½ cup of water. Cook this for about 10 minutes. The smell of cooking cilantro is absolutely heavenly, so enjoy it.

5. Heat 1 Tbsp of coconut oil in a heavy-bottomed small skillet. When the oil is hot, add the urad dhal and cook this for a couple of minutes till the dhal turns golden. If it browns too quickly (in less than 30 seconds), your oil was too hot. If this happens, throw it out and start over. When the dhal is a pretty golden brown, add the coconut and chillies. Let them heat through and then turn off the heat.

6. Allow this coconut mixture to cool a bit and then blend it with ½ cup of water to a fine paste.

7. Now combine the dhal, boiled cilantro, and the ground coconut mixture. Add the remaining 1/2 tsp of salt, stir to combine well and cook it for about 10 minutes on low heat – this allows all the flavors to marry.

8. Once you have tempered the dhal (process below), add 1 Tbsp of fresh lime juice. Stir and serve.

Tempering:

1. Heat the 1 ½ Tbsp coconut oil in a heavy-bottomed small skillet

2. When the oil’s hot, add the mustard seeds and allow them to pop.

3. Once they’re almost done popping, add the cumin seeds, curry leaves, and asafoetida. Cook for about 10 seconds and add this tempering mixture to the dhal.

Stir everything together, turn off the heat, and enjoy the dhal with a rice or bread of your choice; you can also enjoy it plain, like a soup. The night I made it, we had it with plain white rice and the Potateem Curry I gave you the recipe for several weeks ago. I know, carbs on carbs, but this is a combination I absolutely love.

My favorite is probably the shower head. My local jugaadu fix, for spice wimps like me (looking at you, Beth!) is, "Ah, the bird's-eye chili again--time to reach for the mild green chilis." And I have a question: often I hear "urad dhal" referring to black lentils, but here it's referring to white ones. Are they black lentils with their hulls off, or are they two different kinds of lentils, both called "urad"? Thank you for the pictures, by the way--very helpful for such moments. PS I made the tomato chutney again last night; I've been using canned tomatoes this time of year because the fresh ones aren't good yet. Still fantastic!

Nice one! I wouldn't have thought of coriander as a main ingredient in porichakozhambu.

My favourite jugaad story is about the guy whose car broke down in the middle of the desert and he fixed it using - don't miss this - using a mixture of well chewed chewing gum and raisins! Apparently it set like cement in the dry desert heat and he made it back to safety!