I learned to whistle when I was 8 or 9. My parents realized I was pretty good at it when were in Aden. And not being the girls-don’t-whistle kind of parents, they encouraged it. Every week, sometimes twice a week, the family would go to the Aden Refinery Club, or the ARC, with my parents’ good friend Greg. Always on a Friday morning, first for a swim at the beach and then to the club for lunch. A beer for the parents, freezing cold orange juice for my brother and me, and kebabs and chips for lunch. And occasionally for a week day dinner, if we were lucky; my brother and I absolutely loved it. My parents didn’t drive; Greg had a fancy car he’d drive us all in. And in the back of the car, both on the way there and the way back, we’d listen to music. Usually western classical. This is where I learned to love Beethoven’s symphonies, Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik is still my favorite Mozart, Vivaldi, Bach. And Johann Strauss II. I loved Strauss, and would whistle with the car stereo, Strauss’s waltzes and polkas. Listening to them today can take me right back to being that nine-year old in the back of Greg’s black Mercedes, the nine-year old who wanted to someday marry someone with a black Mercedes.

I haven’t whistled along to one of Strauss’s waltzes in ages and ages. Somewhere along the way, I developed an interest in old Hindi film songs. Not from the Bollywood of today; that, for the most part, I can’t stand. Yes, I am now that old person. No. It is the songs from the 50s and 60s, most based on classical music.

India lost an icon at the beginning of this month. Lata Mangeshkar, whose singing career spanned a stupendous 7 decades, is almost synonymous with old Bollywood. And I have spent much time the past couple of weeks listening to old film songs. Now to be honest, I have never been a huge fan of Lata Mangeshkar’s voice – too high-pitched and shrill for me. I have always preferred voices with more girth. But the music and songs she (among others) sang, despite the voice, hold a special place in my heart. Particularly the songs based on classical music. Or the songs that are poetry, often Sufi poetry, set to music. They are what I turn to when I am nostalgic for India. Not home, necessarily, but India. A certain kind of nostalgia, the kind induced by a glass of wine.

I know I am far from alone in this love for old Hindi film songs. And I have often wondered when it started. My parents didn’t play much film music at home – my dad can’t stand Hindi, and except for the odd old Raj Kapoor song, he has no time for film music; he’s a purist. My mum is fonder of old film music, but I don’t remember her playing much either. Both shared their love for classical music, Carnatic, in specific, with me.

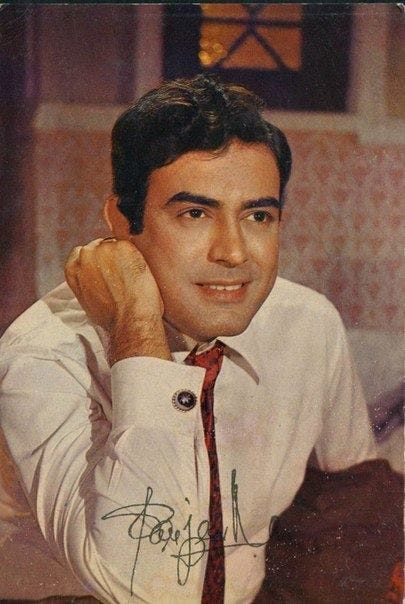

So where did my fondness for film music come from, then? Boarding school, perhaps? This is when I discovered Hindi films. We were allowed to watch TV just on the weekends; a TV would be pulled out of wherever it was stored and put out in the courtyard on a sunny day, and in one of the corridors on a rainy one. All the girls would gather round it, sitting on the ground or floor. On Sunday evenings, there would be the week’s Hindi film, and watching these, I fell in love for the first time (well, not counting the gorgeous Hungarian boy, Attila, on whom I’d had the biggest crush when I was 11; this was in Aden; he had been 17, I think, and didn’t know I existed). My Hindi movie loves were Shashi Kapoor and Sanjeev Kumar. The former – well he was absolutely gorgeous. The latter wasn’t, at least not my idea of good looking. So I’m not sure why he won me over.

Shashi Kapoor in his heyday

And Sanjeev Kumar in his

There was this one particular Sunday when the movie slotted had both my heartthrobs in it. It was exam week, and nobody else wanted to watch. Me being me, I’d finished my studying early. I begged and begged for some of my friends to keep me company. Don’t you understand? It’s got both of them! Please? I’ll help you study later? Nope. So watched it alone, I did. Didn’t enjoy it as much.

Now I didn’t watch the movies during my first few weeks at boarding school, my knowledge of Hindi being extremely limited. But it soon became an important part of our weekend rituals. The movies would go on forever – being all too often punctuated by long spells of advertisements. And we’d sit and laugh together and make fun of the intense, absolutely over-the-top drama, typically focusing around a love story that went horribly wrong (for a thousand different reasons) and spout out lines like “yeh meri izzat ka sawal hey” – it’s a matter of my pride/honor/reputation. A line, it seemed, that was a part of the plot of every single Hindi movie we watched. And we’d hum along with the songs – because of course, song and dance are central to any Bollywood movie. And perhaps my love for the music comes from these memories. And my friends discovered that I loved to whistle.

The other thing the Hindi movies gave me is the language. Growing up in India, particularly in South India, multilingualism is a given. Well, at least it was. There was the home language – in my case, the home languages, then the language that the auntie in the flat below us spoke, then the language that the girl or lady coming to help with the housework spoke, and the language that the shopkeeper uncle down the road spoke. And we learned to speak them all. This was pretty typical. In my household, Hindi wasn’t among anyone’s repertoire, so I didn’t naturally acquire it, as I did Tamil, Kannada, and Telugu.

It wasn’t till much later, when I was 37, when my parents and I took a trip to Agra to see the Taj for the first time that I discovered I could speak a bit of Hindi, more than I had given myself credit for. My dad expressed astonishment at how easily pleasantries in Hindi seemed to roll off my tongue – this nice old man at one of the entrances and I chatted; I might even have flirted mildly. I have to admit, I was astonished, too. Guess those movies taught me more than I thought.

The multilingualism that was central to my everyday existence for the first few years of my life, however, rapidly receded when the family went back to Britain, when I was six or seven. English took over.

Today, I have conversational fluency in Tamil and Kannada. And I don’t read and write them. When I had my son, I spoke to him in Kannada for the first year or so. And then soon realized that I simply don’t have the requisite kid vocabulary. Dinosaurs and trucks and train parts? That’s just English for me. Tamil is even more complicated than Kannada because it is diglossic – meaning there are two distinct varieties of the language – the colloquial variety and the high variety. I understand very little of the high variety. Academic vocabulary in any language other than English is non-existent. So as loath as I am to admit it, my children are monolingual.

I am grateful for the facility I do have in my Indian languages, Tamil, Kannada, and Hindi. The Telugu from my childhood never came back; I do understand a good bit of conversational Telugu, but don’t speak any. And when I listen to music today, I so wish I could understand more.

In urban India today, I’d wager, there are more and more children like my children, who are increasingly being raised monolingual. Or like me, with limited proficiency in a language other than English. It is what it is.

I’ve written before about nostalgia associated with the rain, with train trips, with picnics. And today, with music. Whatever the source of the nostalgia, it is always also connected with fried food. So today’s recipe is just that – fried vegetable fritters. Pakodas. Which have come to be known as Pakoras in the western world. The particular “d” in the word is very far from any English “d”, and an English “r” is a close enough substitute – based just on the relationship of the tip of the tongue to the upper palate in the production of said sounds. So Pakoras, they have become, but Pakodas they’ll be in this recipe.

Cabbage and Onion Pakodas with a Mint and Cilantro Chutney. Which I am eating as I type this, listening to old Lata Mangeshkar songs. Whistling in between bites.

Cabbage and Onion Pakodas

Ingredients (makes about 20 pakodas; vegan; vegetarian; gluten-free)

1. 2 cups shredded cabbage

2. 1 cup finely sliced onions

3. 1 cup chopped cilantro

4. 1 tsp turmeric

5. 2 tsp Kashmiri chilli powder

6. ¼ tsp asafoetida

7. 1 ½ tsp salt

8. ¾ cup chickpea flour

9. ¼ cup rice flour

10. About ½ cup water

11. Oil to fry

Method

1. Mix the cabbage, onion, cilantro, turmeric, chilli powder, asafoetida, and salt together. Let the mixture to sit for about 10 minutes to allow the veggies to release some water. This will reduce the amount of water you need to add to the mixture in the next step.

2. Now add the chickpea and rice flours, and mix well. Sprinkle on the water slowly and mix, to allow the mixture to come together. You don’t want a batter – you just want the veggies to be held together by the flour and a wee bit of water.

3. Heat the oil in a heavy skillet

4. Make the pakodas using your fingers. This involves taking about a tablespoon or a bit more of the mixture onto the tips of your fingers and slightly flattening it between your fingers and thumb, and then and allowing it to drop into the hot oil. You don’t want to form balls, as the pakodas should be free-form. What you want is as much surface area as possible to hit the oil – which will not happen if you make balls to fry. Forming them with your fingers allows for a crisp surface, an altogether far nicer mouth feel.

5. Fry the pakodas, several at a time (but not too many to overcrowd your pan), on medium heat, for about 5-6 minutes.

6. Lift them out of the oil with a slotted spoon and put them on a sheet of kitchen towel to absorb any extra oil. Serve hot with the mint and cilantro chutney.

Mint and Cilantro Chutney

Above all other recipes I have given you so far, this is the one that is most flexible. This is a combination and these are quantities that work for me; you can adapt any of the quantities to suit your palates. If you have an aversion to cilantro, you can leave it out and use just mint. This chutney can be used as a marinade for meats or fish, or makes the most amazing chutney and cucumber sandwiches – a thing of every Indian of my generation’s childhood.

Ingredients (makes about 2 cups of chutney; vegetarian; gluten-free)

1. 2 packed cups mint leaves (including the smaller stems)

2. 2 packed cups cilantro – stems and all

3. 2 green chillies – or as per your taste

4. 2 large cloves garlic – the garlic in this recipe is raw, so you can choose how much or how little you want.

5. 1 ½ tsp salt

6. 2 Tbsp fresh lime juice

7. ¾ to 1 cup water

8. Optional: 2 Tbsp yoghurt

Method

1. Blend all the ingredients (except the yoghurt) together to form a smooth-ish paste. If you are using yoghurt, mix it in at the end. It adds a lovely creaminess.