It always smells the same. Food smells, usually saaru (the Kannada word for rasam), and whiffs of the smoke from the wood burning stove out back. The stove that faithfully heats up huge vats of water with which we bathe in the outdoor bathroom. My eyes dart to the corner of the room when we enter it, and there it is. The large bamboo pole used to hoist wet clothes up to the clothes line hung high up in the room. Try as I might, I can never get the clothes to unfold neatly on the line with that pole. Ajji’s house. I can still taste her saaru. And smell the smoke from the wood heating the vat of water.

My mum’s mum. Ajji never smiled. She died when I was 8 or 9, and I don’t remember much of her. Other than her saaru. And that she never smiled. Always looked stern, uncompromising. And had, I am told, a temper.

Now while a large part of that was her personality (I am all too aware that I have her genes), I’d wager circumstance also had a lot to play with her demeanor, her outlook.

She was married when she was 12, bore 10 children, looked after 11, the 11th being a nephew who had been orphaned when he was two weeks old, and did most of this single-handedly. My grandfather was in the Indian army, fought in WWII, and was away for years. And then died when my mum, the second youngest of the 10 kids, was 18. So the old battle-axe did have to deal with a lot. At a time when circumstances for women were, well, hard would be an understatement. Hindu women are supposed to play a supporting role to their husbands, and she played one hell of a supporting role in addition to the only main role in the family for years. I cannot not appreciate her for the strength she must have had. Despite the fact that she didn’t smile.

But both personality and circumstance possibly dictated certain choices she made; the kind of house she kept; the observance of madi (/mɑɖɪ/). It means purity. A Brahmin “purity” ascribed to certain people; a “purity” that is ascribed to one who bathes before they can pray; a “purity” that can be tainted by the mere touch of another, unbathed person. Even a child. A “purity” that is needed before any food can be cooked. A “purity” that gives people who claim to possess it a superiority over others.

A “purity” that renders another untouchable.

And a “purity” that cannot, under any circumstances, be obtained by a woman during her monthly period. She is, at that time, an untouchable. She sleeps separately – in very traditional houses, in a room outside the main house; an outhouse. She eats separately, can’t touch even the utensils used by the rest of pure humanity in the household, bathed or otherwise. Her bleeding makes her, in a word, dirty. And her impurity means, of course, that she is not allowed anywhere near a place of worship.

My parents never practiced madi; at least my mum never did, in our household, to my knowledge, and they certainly didn’t expect it of me. I only experienced it once, when I was 16 or 17, a naïve 16 or 17. I had to take a trip to Pondicherry, a city in Tamil Nadu, in order to sit an exam, and had a couple of days after to see the sights. I was staying with a former student of my dad’s, and had the misfortune of having a period during my visit. I hadn’t gone prepared, and needed to know where to procure necessities. The remaining duration of my trip was like nothing I had ever experienced, and haven’t experienced since. The former student, no doubt, out of the utmost respect for my dad, kept me out of the house an entire day, showing me Pondicherry, just in order that I wouldn’t have to experience madi in its entirety. Once we returned to her home, she very uncomfortably told me that they were a very traditional household. For the next day, I was a complete untouchable.

Now there are several in my extended family who practice madi even today. And they explain it as giving a woman time during her period, an opportunity to rest, not to be burdened by the everyday tasks that demand her every waking second the rest of the month. This is how it originated, they try to explain.

I choose not to buy this explanation; I don’t have a spirit nearly generous enough. While it might well have arisen because of a concern for a woman’s well-being, now, it is connected, pure and simple, with impurity. With untouchability. The same reason there are no women priests – apparently even god is not great enough to remove a woman’s impurity while she bleeds. There are even temples in India where women aren’t allowed at all. At all. Ever.

And the system is perpetuated. Traditions.

And traditions are all well and good. If they don’t perpetuate a flawed system. Based on our (flawed) interpretation of religious texts. Irrespective of which religion, I might add. Just like our interpretations of religious texts dictate how and what we should eat, how we should dress, our professions, who we should marry. The list is endless.

So women can’t go into a temple to worship if they are menstruating. Even a temple devoted entirely to a female deity. Ironic much?

Ah but you are talking about a generation ago, you might argue. Things have changed since your Ajji’s time. Or even since your time in Pondicherry? Surely?

But how much have times changed? Every time I visit home, I am astounded by how much things have changed. Seemingly. Astounded by the now upper-middle class, a class borne during the dot com boom. A class that grew with the Indian economy. Today, a class of young twenty-somethings. I am astounded by the freedoms they exhibit, the freedoms they seem to have – in their clothing, in their choice of food and drink, in their seemingly endless disposable incomes. The Indians who know how to make kombucha better than they do how to make idly or dosa batter. Those that exalt the beauty of fermented foods like kimchi, forgetting our own incredible history with fermentation. But this is in very urban Bangalore. And other urban large cities.

And just when I think things have changed altogether, at least in urban India, (and not necessarily for the good, my mind hastens to add), I read an article like More than Wives and Wombs by Vaishna Roy, that appeared in The Hindu on the 15th of October. A short article based on a Twitter conversation (yes) bemoaning the “uppity” attitudes of young Brahmin girls these days who don’t want to marry, or gasp, don’t want to have kids! And the poor long-suffering good Brahmin men, the future priests. How are they supposed to get through lives without dutiful and faithful wives? How are they expected to fulfill their priestly responsibilities without help? Without someone to clean for them? Without someone to bear their offspring? Where would future priests come from?

And I realize little has really changed. Superficially? Sure. And for some people more than others. But for the majority, little has really changed. Men make the rules…based on scripture, of course. How can they question that? Women follow. And older women lament the downfall of younger women not wanting to follow in their footsteps. And give younger women a hard time for wanting to forge their own ways. Women are still expected to put the needs of others above theirs; their roles are simple – to marry and procreate. And be dutiful wives. Above anything else. Like Ajji.

A divorced man: Oh poor chap, he should re-marry so he can have some help. A divorced woman: What’s wrong with her? A widowed man: Same, poor, poor chap. A widowed woman: Bad luck – as in, she is bad luck, stay away from her. Even today.

Are there exceptions? Oh absolutely. Many. But that is just what they are. Exceptions.

Ajji, though? Didn’t take shit from anyone for being widowed. Or for anything else. And irrespective of how much I disagree with choices she made, and how much I wish she had smiled a bit, I am grateful for her strength. I know I have some of it.

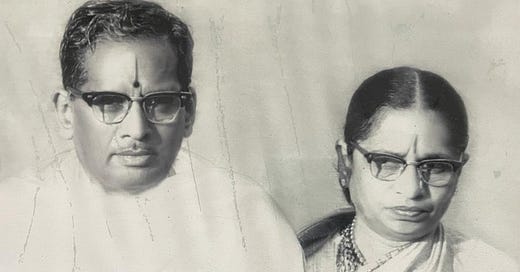

My Ajji and Tata; taken in the early 1960s, I would guess.

I have a feeling, however, that she would have frowned on a lot of choices I have made in my life. My omnivorous diet might not even be at the top of her list of grievances. And so on that note, here is a chicken curry for today. Chandri’s chicken curry. The first kind of chicken curry I experimented with years ago when I first ventured into the non-veg world, and a recipe that has undergone many changes since. A simple, yoghurt-based curry that I have made my own.

Chandri’s Chicken Curry

Ingredients (serves 4-6)

1. 2lb or about 1kg of chicken – I use thighs and drums, skin on. You can use any pieces of your choice.

2. 3 Tbsp finely chopped garlic

3. 2 Tbsp finely chopped ginger

4. 2-3 green chillies – or as per your choice – finely chopped

5. 1 cup yoghurt

6. 1½ tsp turmeric

7. 1 Tbsp coriander seeds

8. 1 tsp fennel seeds

9. 2 cups finely diced onions

10. 1 cup chopped ripe tomatoes

11. 1 Tbsp + 1 tsp cumin seeds

12. 3 Tbsp vegetable, sunflower, safflower, or any neutral oil

13. 2 tsp salt

14. ½ cup chopped cilantro (optional)

Method

1. Marinate the chicken in the yoghurt, ginger, garlic, chillies, and ½ tsp of the turmeric

2. Grind 1tsp of the cumin seeds, 1 tbsp coriander seeds, and 1 tsp fennel seeds together in a spice grinder. If you don’t have a spice grinder, you can use a mortar and pestle. Make as fine a spice mix as you can.

3. Heat the oil. When it is hot, add the cumin seeds – they splutter. Add the rest of the turmeric.

4. Add the chopped onions, and sauté for about 10 minutes on low-medium heat. They should just start browning.

5. Now add the chopped tomatoes and the ground spice mixture. Add ½ cup of water to this, and cook together on low-medium heat for about 10 minutes. You want to cook all this together till the oil starts separating. Could you cook it for less time? Sure, but the flavors won’t develop as well. But if you simply don’t have the time, skip this step and add combine steps 5 and 6. The curry will still be good - just not as good.

6. Now add 1 tsp Kashmiri chilli powder to the cooked mixture and add the chicken, marinade and all.

7. Add 1 tsp salt and cook with a lid on. Stir occasionally. Cook till chicken is tender. How long it takes depends entirely on the size of your pieces of chicken.

8. Add chopped cilantro, stir, and serve hot with rice or a bread of your choice.

Made me laugh out loud when I saw how much she frowned!

Lovely read and wow I've learnt a lot in such a small moment.

Sending you hugs and after I finish this exclusion diet and I can eat onions and garlic again I will definatley make it !!

Absolutely one of my favorite chicken curries!