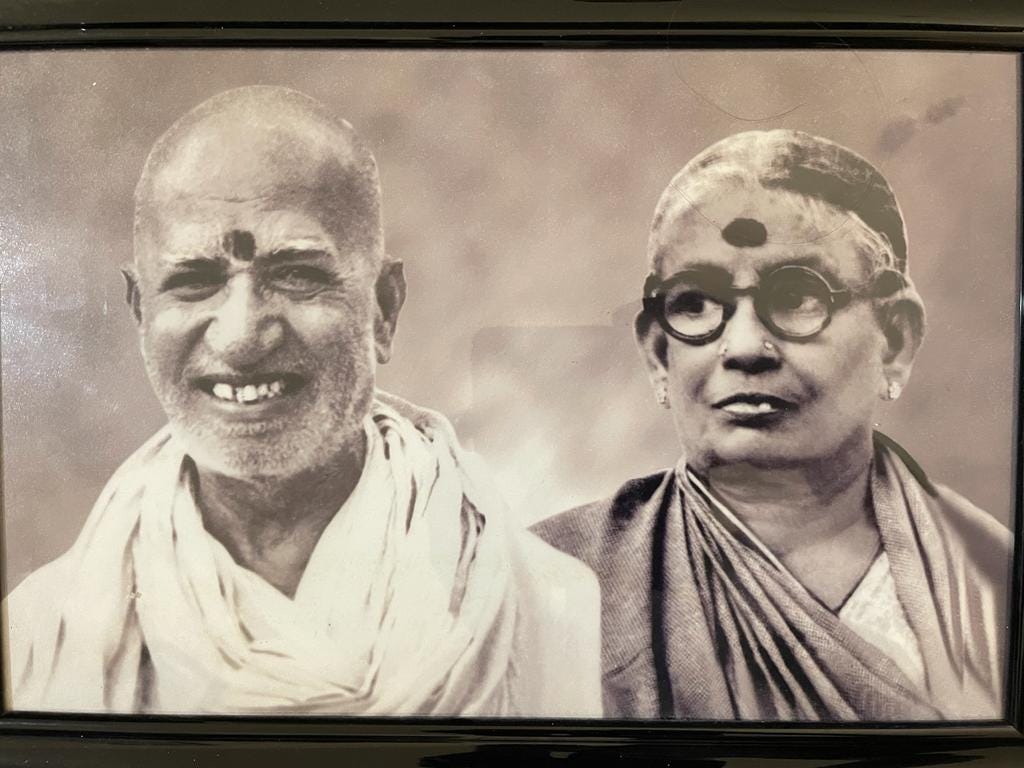

My paternal grandfather, Tata (/t̪ɑːt̪t̪ɑː/), is the only grandparent I got to know a little; my maternal granddad died when my mum was a teenager; my two grandmothers died when I was 8 or 9. Tata lived till he was 89, and died when I was a student at the Bishop Cotton Girls’ school. I was 13 or 14, and was at boarding school. In my short time at Bishop Cotton’s before he died, I got to know him a little through the letters he’d write me. Blue inland letters, different from the bigger blue aerograms I’d receive from my parents abroad. Tata’s eyesight was failing, but he would insist on addressing the letters himself (my aunt with whom he lived would more clearly write the address above his scrawl). I’d love seeing a letter from him waiting by my lunch plate – that’s where we received our mail, in the dining hall. And I’d long to be done with lunch those days so I could tear outside and devour the letters.

He was tall - 6 foot. And that’s important because my paternal grandmother, Paati (/pɑ̪ʈʈɪ/), wasn’t. 4 foot 10 inches, if that. And guess who every one of their 8 children took after? Yup. Strong, her genes were. They were married for more than 55 years before she died, and she did everything for him. And while I did get to know him a little those few months at boarding school before he died, I wish I had had the opportunity to get to know him better, to ask him so many questions, not the least of which would have been why Patti had given up her music for him after she married. Because that’s the way it was then, I have been told when I ask other people; women were dutiful wives, above all.

My dad tells the story of how mealtimes were in their household. Paati would always serve Tata first, and only after he was completely done would she sit down to her own meal. And during his meal, she would do everything to make sure he was comfortable. Like this: we use our fingers to eat with in India; we mix the rice (carb of choice about 90% of times in South India) with whatever lentil preparation there is, then scoop the rice-dhal mixture into a ball and eat that along with whatever else there is. So apparently Tata would often ball up the rice and dhal, create a cavity in the middle, into which Paati would spoon just enough of whatever else there was that day - vettakozhambu, a spicy tamarind-based sauce, being a particular favorite. To create an absolutely stupendous bite of food. (And I know this because I love similar bites of food today.) So. Why couldn’t he do this for himself? Why didn’t they eat together? More questions I would have asked him.

And why didn’t she sing anymore? I hear she had had a terrific voice and loved music. Gave it all up. My dad definitely inherited her musical genes in addition to her short genes.

Now obviously women’s roles have changed, both in India, and in the west, both out of some (begrudging, in many contexts?) recognition that women need to be able to do what they want, as well as (perhaps more, and no, I am not cynical) out of necessity – changing social pressures, changing economies. I don’t know anyone in the west (or even in India, for that matter), who has the luxury today of living in a single-income household. And women have risen to the challenge. And how has society helped? Ah, that’s where things get hairier, no matter how loud and raucous the protestations to the contrary may be. How much easier has it become for women to lead more satisfying lives? To lead more fulfilling lives? Or to find a balance, or try and find a balance between their different worlds?

I have chosen to delve into this question by moving to to the other side of the world, to the US, where I spent a large part of my early adulthood. Why?

Because even in my early student days in the US, I wondered at the ads I saw on TV. There was one for a vacuum cleaner. Or maybe it was for a laundry detergent. Or maybe there were two different ones; the ad had a father looking after his littles - there were two of them, while the woman of the household was away at work. The ads portrayed the utter ineptitude, and that’s putting it mildly, on the father’s part, to take care of the kids’ basic needs - food and cleanliness. The ad was meant to be funny, of course. And to me, it was, well, not. Confusing, perhaps. Hadn't I moved to a country that prided itself on its feminist views?

And why else have I chosen to talk about the US?

Because the US is where I got my first job.

Because the US is where I learned very quickly how in all walks of life women get paid less than men for the same job. Even in academia, the supposed bastion of liberalism, progressive thought. I won't bore you with statistics - the AAUW has plenty.

Because the US is where I realized, early in my university career, the difficulty of balancing a home life with work life. Where I had a conversation with a colleague about tenure, worrying about it because I was thinking about children. And was advised to possibly delay tenure by a year or two.

Because the US is where, again, early in my university career, I very much wanted to climb the administrative ladder. And realized the difficulties of pursuing that dream and wanting a family at the same time.

Because the US is where I bought my first house. One that had to have my then-husband’s name first on the papers, because well…even though I was the primary earner.

Because the US is where when I got divorced and sought to change my name on my driver’s license, I was asked by the clerk at the local DMV where on my divorce papers it said I was allowed to revert to my maiden name. Oh, hardly representative, you might argue. Perhaps. But not the exception, either.

Because the US is where I got married again and had my first child. And before the kid came, I realized that there was no help, no maternity leave. None. I was incredibly fortunate because I had a good and kind boss. And unofficially, he gave me course releases which meant I had a much lighter load than I otherwise would have. And excused me from all committee work for a semester. Which made those first six months with my son truly wonderful. Brian, I still owe you.

Because the US is where after the first kid, I realized the utter impossibility of a second if we wanted any quality of life.

And mostly because the US is from where the loudest voices condemning, decrying other cultures for their treatment of women emanate. Voices so full of sound and fury, signifying…well maybe not nothing, but not much? And I don’t have to go anywhere near what’s going on with women’s rights right now to say this.

And because the US is where when even the idea of children became a reality for me, any dreams of moving up the administrative ladder had to be laid to rest. Because that is the kind of parent I wanted to be, and I knew I simply couldn’t be both. So I gave up something I had wanted.

And I am most certainly not complaining. Because despite all this, I am among the very, very privileged. Simply because for the most part, I have had the luxury of choice. But how many women (even in the US) do? Are they so different from my Paati? Even today.

And because I am privileged with choice, I am thrilled to occasionally pull a Paati and serve my husband, and even add spoonfuls of vettakozhambu or gojju to his dhal and rice. He grimaces, and then returns the favor.

So here is the recipe for an onion gojju (/godd͡ʒʊ/), another tamarind-based sauce, which goes amazingly well with plain dhal and rice to make the kind of bite that Tata loved (in addition to being amazing with other things). Now Tata would NOT have had this particular onion gojju – not Brahmin enough because of the onions. Oh well.

This onion gojju shouldn’t be eaten as a soup (too acidic on its own), but can be used as an accompaniment to any number of things. My favorite way of eating this, aside from along with dhal and rice, is with a rava dosa – a dosa made of semolina and rice flour. The recipe for that will be next week. For today, here’s the onion gojju.

To make things easier for you, I have used a tamarind concentrate for this, something easily available in all Indian markets. Before using it, check the ingredients for salt content. If it does have salt in it, reduce the amount of salt in the dish, as I have indicated below.

Onion Gojju

Ingredients: (serves 4-6 as a side to rice or a bread of some sort; vegan; vegetarian; gluten-free)

1. 3 ½ Tbsp tamarind paste – mixed with 4 cups of water. Make sure there are no lumps at the bottom.

2. 2 ½ cups finely diced onions

3. 3 green chillies or 2 jalapenos diced fine (or more or less as per your liking)

4. 2 Tbsp oil

5. 1 tsp mustard seeds

6. ½ tsp fenugreek seeds

7. ½ tsp turmeric

7. 3 squeezes of asafoetida (about ¼ tsp)

8. 2 sprigs of curry leaves

9. ½ tsp salt (because the tamarind paste already has salt. If your tamarind paste doesn’t have any salt in it, you’ll need 1 ½ tsp of salt)

10. 1 tsp Kashmiri chilli powder OR ½ tsp cayenne pepper or regular chilli powder

11. 1 tsp ground coriander seed

12. 2 ½ tsp sugar or jaggery

Method

1. Mix the tamarind paste with the water. Some tamarind pastes come with a film of oil on top; when spooning it out, try and get as little of the oil as possible.

2. Heat the oil in a heavy-bottomed pan. When the oil is hot, add the mustard seeds.

3. When the mustard seeds are almost done popping, add the fenugreek, asafoetida, curry leaves, turmeric, and chillies. Cook together for about 10 seconds.

4. Add the diced onions and the salt. Saute for about 6 minutes on low-medium heat. You don’t want the onions to caramelize at all, just to soften.

5. Now add the ground coriander seed and Kashmiri chilli powder or cayenne pepper, and cook together for 3 minutes.

6. Now add the tamarind water. Allow it to come to a boil and then simmer for about 10 minutes.

7. Add the sugar or jaggery and cook for an additional minute. Don’t skimp on the sugar - the dish needs it to balance the tartness of the tamarind. If, at this stage, you want to thicken the gojju a bit, mix 1 tsp rice flour or chickpea flour with ¼ cup of water, and add this slurry to the gojju. I don’t like a very thick gojju, so usually skip this step. Cook for 2-3 minutes and turn off the heat.

8. This is the first recipe I have given you that you can’t eat plain – like a soup. It is too acidic, and needs a carb to go along – either a bread or rice. Or, as I served it, a great semolina and rice flour dosa, called a lacy dosa in my household – a recipe for which I will give you next week. So for this week, enjoy the gojju with bread or plain rice. Or as my Tata did, with some rice and plain dhal.

Loved the read and took my own trip zig zagging down the lanes of nostalgia.

Have not made the gojju in a really long time and am looking forward to using your recipe for lunch today .

Insightful and enjoyable. Read it with delight.